My SxSW session with Sally Applin, PolySocial Reality and the Enspirited World, seemed to be well received. The group that attended was well-engaged and we had a fertile Q&A discussion. Sally focused her keen anthropological lens on the study of our increasingly complex communications with her model of PolySocial Reality; for more on PoSR see Sally’s site. [Update 3/20: Sally posted her slides on PolySocial Reality]. My bit was about the proximate future of pervasive computing, as seen from a particular viewpoint. These ideas are not especially original here in 02012, but hopefully they can serve as a useful nudge toward awareness, insight and mindful action.

What follows is a somewhat pixelated re-rendering of my part of the talk.

This talk is titled “in digital anima mundi (the digital soul of the world).” As far as I know Latin doesn’t have a direct translation for ‘digital’, so this might not be perfect usage. Suggestions welcomed. Anyway, “the digital soul of the world” is my attempt to put a name to the thing that is emerging, as the Net begins to seep into the very fabric of the physical world. I’m using terms like ‘soul’ and ‘enspirited’ deliberately — not because I want to invoke a sacred or supernatural connection, but rather to stand in sharp contrast to technological formulations like “the Internet of Things”, “smart cities”, “information shadows” and the like.

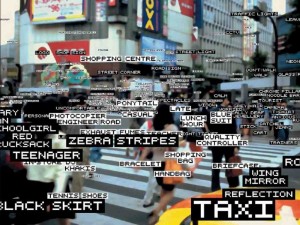

The image here is from Transcendenz, the brilliant thesis project of Michaël Harboun. Don’t miss it.

The idea of anima mundi, a world soul, has been with us for a long time. Here’s Plato in the 4th century BC.

Fast forward to 1969. This is a wonderful passage from P.K. Dick’s novel Ubik, where the protagonist Joe Chip has a spirited argument with his apartment door. So here’s a vision of a world where physical things are animated with some kind of lifelike force. Think also of the dancing brooms and talking candlesticks from Disney’s animated films.

In 1982, William Gibson coined the term ‘cyberspace’ in his short story Burning Chrome, later elaborated in his novel Neuromancer. Cyberspace was a new kind of destination, a place you went to through the gateway of a console and into the network. We thought about cyberspace in terms of…

Cities of data…

Worlds of Warcraft…

A Second Life.

Around 1988, Mark Weiser and a team of researchers at Xerox PARC invented a new computing paradigm they called ubiquitous computing, or ubicomp. The idea was that computing technologies would become ubiquitous, embedded in the physical world around us. Weiser’s group conceived of and built systems of inch-scale, foot-scale and yard-scale computers; these tabs, pads and boards have come to life in today’s iPods, smartphones, tablets and flat panel displays, in form factor if not entirely in function.

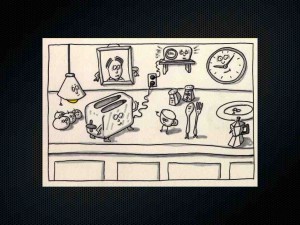

In 1992 Rich Gold, a member of the PARC research team, gave a talk titled Art in the Age of Ubicomp. This sketch from Gold’s talk describes a world of everyday objects enspirited with ubicomp. More talking candlesticks, but with a very specific technological architecture in mind.

Recently, Gibson described things this way: cyberspace has everted. It has turned inside out, and we no longer go “into the network”.

Instead, the network has gone into us. Digital data and services are embedded in the fabric of the physical world.

Digital is emerging as a new dimension of reality, an integral property of the physical world. Length, width, height, time, digital.

Since we only have this world, It’s worth exploring the question of whether this is the kind of world we want to live in.

A good place to begin is with augmented reality, the idea that digital data and services are overlaid on the physical world in context, visible only when you look through the right kind of electronic window. Today that’s smartphones and tablets; at some point that might be through a heads-up display, the long-anticipated AR glasses.

Game designers are populating AR space around us with ghosts and zombies.

Geolocative data are being visualized in AR, like this crime database from SpotCrime.

History is implicit in our world; historical photos and media can make these stories explicit and visible, like this project on the Stanford University quad.

Here’s a 3D reconstruction, a simulation of the Berlin Wall as it ran through the city of Berlin.

Of course AR has been applied to a lot of brand marketing campaigns in the last year or two, like this holiday cups app from Starbucks.

AR is also being adopted by artists and culture jammers, in part as a way to reclaim visual space from the already pervasive brand encroachment we are familiar with.

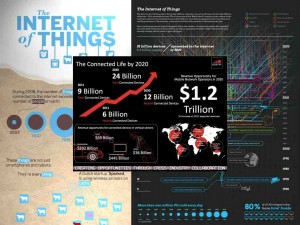

We also have the Internet of Things, the notion that in just a few years there will be 20, 30, 50 billion devices connected to the Net. Companies like Cisco and Intel see huge commercial opportunities and a wide range of new applications.

An Internet of Things needs hyperlinks, and you can think of RFID tags, QR codes and the like as physical hyperlinks. You “click” on them in some way, and they invoke a nominally relevant digital service.

RFID and NFC have seen significant uptake in transit and transportation. In London, your Will and Kate commemorative Oyster card is your ticket to ride the Underground. In Japan, your Octopus or Suica card not only lets you ride the trains, but also purchase items from vending machines and pay for your on-street parking. In California we have FasTrak for our cars, allowing automated payment at toll booths. These systems improve efficiency of the infrastructure sevices and provide convenience to citizens. However, they are also becoming control points for access to public resources, and vast amounts of data are generated and mined based on the digital footprints we leave behind.

Sensors are key to the IoT. Botanicalls is a product from a few years ago, a communicating moisture sensor for your houseplants. When the soil gets dry, the Botanicall sends you a tweet to let you know your plant is thirsty.

More recently, the EOS Talking Tree is an instrumented tree that has a Facebook page and a Twitter account with more than 4000 followers. That’s way more than me.

This little gadget is the Rymble, billed by its creators as an emotional Internet device. You connect it with your Facebook profile, and it responds to activity by spinning around, playing sounds and flashing lights in nominally meaningful ways. This is interesting; not only are physical things routinely connected to services, but services are sprouting physical manifestations.

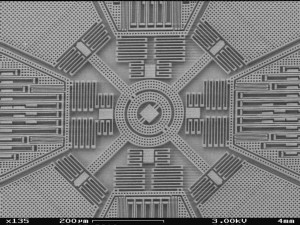

This is a MEMS sensor, about 1mm across, an accelerometer & gyroscope that measures motion. If you have a smartphone or tablet, you have these inside to track the tilt, rotation and translation of the device. These chips are showing up in a lot of places.

Some of you probably have a FitBit, Nike+, FuelBand, WiThings scale. Welcome to the ‘quantified self’ movement. These devices sense your physical activity, your sleep and so on, and feed the data into services and dashboards. They can be useful, fun and motivating, but know also that your physical activities are being tracked, recorded, gamified, shared and monetized.

Insurance companies are now offering sensor modules you can install on your car. They will provide you with metered, pay-as-you-drive insurance, with variable pricing based on the risk of when, where and how safely you drive.

Green Goose wants you to brush your teeth. If you do a good job, you’ll get a nice badge.

How about the Internet of Babies? This is a real product, announced a couple of weeks ago at Mobile World Congress. Sensors inside the onesie detect baby’s motion and moisture content.

Here’s a different wearable concept from Philips Design, the Bubelle Dress that senses your mood and changes colors and light patterns in response.

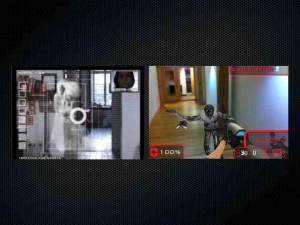

So physical things, places and people are becoming gateways to services, and services are colonizing the physical world. Microsoft’s Kinect is a great example of a sensor that bridges physical and digital; the image is from a Kinect depth camera stream. This is how robots see us.

If a was a service, I think I’d choose some of these robots for my physical instantiation. You’ve probably seen these — DARPA’s Alpha Dog all-terrain robotic pack horse, DARPA’s robot hummingbird, Google’s self-driving cars. You might not think of cars as robots, but these are pretty much the same kinds of things.

Robots also come in swarms. This is a project called Electronic Countermeasures by Liam Young. A swarm of quadrotor drones forms a dynamic pirate wireless network, bringing connectivity to spaces where the network has failed or been jammed. When the police drones come to shoot them down, they disperse and re-form elsewhere in the city.

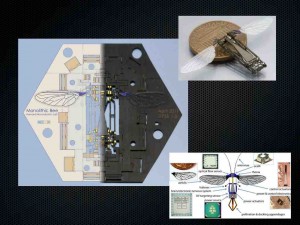

A team at Harvard is creating Robobees. This is a flat multilayer design that can be stamped out in volume. It is designed so that the robot bee pops up and folds like origami into the shape at top right. I wonder what kind of service wants to be a swarm of robotic bees?

On a larger scale, IBM wants to build you a smarter city. There are large smart city projects around the globe, being built by companies like IBM, Cisco and Siemens. They view the city as a collection of networks and systems – energy, utilities, transportation etc – to be measured, monitored, managed and optimized. Operational efficiency for the city, and convenience for citizens.

But we as individuals don’t experience the city as a stack of infrastructures to be managed. Here’s Italo Calvino in his lovely book Invisible Cities. “Cities, like dreams, are made of desires and fears…the thread of their discourse is secret, their rules absurd.”

Back at ground level in the not-so-smart city of today, displays are proliferating. Everywhere you turn, public screens are beaming messages from storefronts, billboards and elevators.

We’re getting close to the point where inexpensive, flexible plastic electronics and displays will be available. When that happens, every surface will be a potential site for displays.

We’re also seeing cameras becoming pervasive in public places. When you see a surveillance camera, do you think it’s being monitored by a security guard sitting in front of a bank of monitors as seen in so many movies? More likely, what’s behind the camera is a sophisticated computer vision system like this one from Quividi, that is constantly analyzing the scene to determine things like the gender, age and attention of people passing by.

A similar system from Intel called Cognovision is being used in a service called SceneTap, which monitors the activity in local nightclubs to let you know where the hottest spots are at any given moment.

You’ve probably seen something like this. It’s worth remembering that our technologies are all too brittle, and you should expect to see more of this kind of less-than-graceful degradation.

In case the city isn’t big enough, IBM wants to bring us a smarter planet. HP wants to deploy a trillion sensors to create a central nervous system for the earth. “The planet will be instrumented, interconnected and intelligent. People want it.” But do we? Maybe yes, maybe no?

So we come back to the question, what kind of world do you want to live in? Almost everything I’ve talked about is happening today. The world is becoming digitally transformed through technology.

Many of these technologies hold great promise and will add tremendous value to our lives. But digital technology is not neutral — it has inherent affordances and biases that influence what gets built. These technologies are extremely good at concrete, objective tasks: calculating, connecting, distributing and storing, measuring and analyzing, transactions and notifications, control and optimization. So these are often fundamental characteristics of the systems that we see deployed; they reflect the materials from which they are made.

We are bringing the Internet into the physical world. Will the Internet of people, places and things be open like the Net, a commons for the good of all? Or will it be more like a collection of app stores? Will there be the physical equivalents of spam, cookies, click-wrap licensing and contextual advertising? Will Apple, Google, Facebook and Amazon own your pocket, your wallet and your identity?

And what about the abstract, subjective qualities that we value in our lives? Technology does not do empathy well. What about reflection, emotion, trust and nuance? What about beauty, grace and soul? In digital anima mundi?

In conclusion, I’d like to share two quotes. First, something Bruce Sterling said at an AR conference two years ago. You are the world’s first pure play experience designers. We are remaking our world, and this a very different sort of design than we are used to.

What it is, is up to us. Howard first said it more than 25 years ago, and it has never been more true than today.

I want to acknowledge these sources for many of the images herein.