The concept video of Google’s Project Glass has whipped up an Internet frenzy since it was released earlier this week, with breathless coverage (and more than a little skepticism) about the alpha-stage prototype wearable devices. Most of the reporting has focused on the ‘AR glasses’ angle with headlines like “Google Shows Off, Teases Augmented Reality Spectacles“, but I don’t think Project Glass is about augmented reality at all. The way I see it, Glass is actually about creating a new model for personal computing.

The concept video of Google’s Project Glass has whipped up an Internet frenzy since it was released earlier this week, with breathless coverage (and more than a little skepticism) about the alpha-stage prototype wearable devices. Most of the reporting has focused on the ‘AR glasses’ angle with headlines like “Google Shows Off, Teases Augmented Reality Spectacles“, but I don’t think Project Glass is about augmented reality at all. The way I see it, Glass is actually about creating a new model for personal computing.

Think about it. In the concept video, you see none of the typical AR tropes like 3D animated characters, pop-up object callouts and video-textured building facades. And tellingly, there’s not even a hint of Google’s own Goggles AR/visual search product. Instead, what we see is a heads-up, hands-free, continuous computing experience tightly integrated with the user’s physical and social context. Glass posits a new use model based on a novel hardware platform, new interaction modalities and new design patterns, and it fundamentally alters our relationship to digital information and the physical environment.

This is a much more ambitious idea than AR or visual search. I think we’re looking at Sergey’s answer to Apple’s touch-based model of personal computing. It’s audacious, provocative and it seems nearly impossible that Google could pull it off, which puts it squarely in the realm of things Google most loves to do. Unfortunately in this case I believe they have tipped their hand too soon.

Let’s suspend disbelief for a moment and consider some of the implications of Glass-style computing. There’s a long list of quite difficult engineering, design, cultural and business challenges that Google has to resolve. Of these, I’m particularly interested in the aspects related to experience design:

Continuous computing

The rapid adoption of smartphones is ample evidence that people want to have their digital environment with them constantly. We pull them out in almost any circumstance, we allow people and services to interrupt us frequently and we feed them with a steady stream of photos, check-ins, status updates and digital footprints. An unconsciously wearable heads-up device such as Glass takes the next step, enabling a continuous computing experience interwoven with our physical senses and situation. It’s a model that is very much in the Bush/Engelbart tradition of augmenting human capabilities, but it also has the potential to exacerbate the problematic complexity of interactions as described by polysocial reality.

A continuous computing model needs to be designed in a way that complements human sensing and cognition. Transferring focus of attention between cognitive contexts must be effortless; in the Glass video, the subject shifts his attention between physical and digital environments dozens of times in a few short vignettes. Applications must also respect the unique properties of the human visual system. Foveal interaction must co-exist and not interfere with natural vision. Our peripheral vision is highly sensitive to motion, and frequent graphical activity will be an undesirable distraction. The Glass video presents a simplistic visual model that would likely fail as a continuous interface.

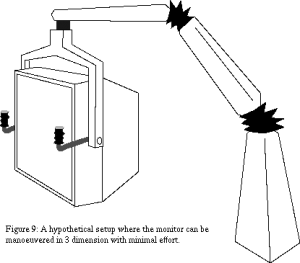

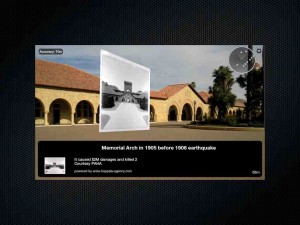

Continuous heads-up computing has the potential to enable useful new capabilities such as large virtual displays, telepresent collaboration, and enhanced multi-screen interactions. It might also be the long-awaited catalyst for adoption of locative and contextual media. I see continuous computing as having enormous potential and demanding deep insight and innovation; it could easily spur a new wave of creativity and economic value.

Heads-up, hands-free interaction

The interaction models and mechanisms for heads-up, hands-free computing will be make-or-break for Glass. Speech recognition, eye tracking and head motion modalities are on display in the concept video, and their accuracy and responsiveness is idealized. The actual state of these technologies is somewhat less than ideal today, although much progress has been made in the last few years. Our non-shiny-happy world of noisy environments, sweaty brows and unreliable network performance will present significant challenges here.

Assuming the baseline I/O technologies can be made to work, Glass will need an interaction language. What are the hands-free equivalents of select, click, scroll, drag, pinch, swipe, copy/paste, show/hide and quit? How does the system differentiate between an interface command and a nod, a word, a glance meant for a friend?

Context

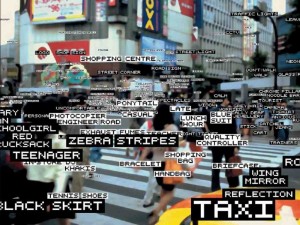

Physical and social context can add richness to the experience of Glass. But contextual computing is a hard problem, and again the Glass video treats context in a naïve and idealized way. We know from AR that the accuracy of device location and orientation is limited and can vary unpredictably in urban settings, and indoor location is still an unsolved problem. We also know that geographic location (i.e., latitude & longitude) does not translate to semantic location (e.g., “in Strand Books”).

On the other hand, simple contextual information such as time, velocity of travel, day/night, in/outdoors is available and has not been exploited by most apps. Google’s work in sensor fusion and recognition of text, images, sounds & objects could also be brought to bear on the continuous computing model.

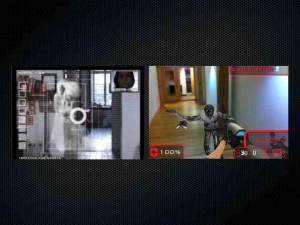

Continuous capture

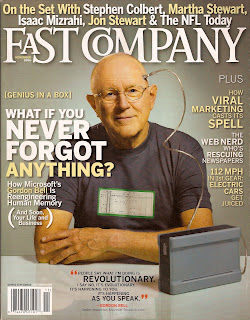

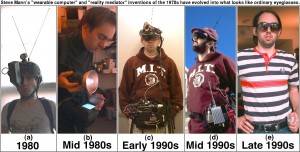

With its omnipresent camera, mic and sensors, Glass could be the first viable life recorder, enabling the “life TiVo” and total recall capabilities explored by researchers such as Steve Mann and Gordon Bell. Continuous capture will be a tremendous accelerant for participatory media services, from YouTube and Instagram-style apps to citizen journalism. It will also fuel the already heated discussions about privacy and the implications of mediated interpersonal relationships.

With its omnipresent camera, mic and sensors, Glass could be the first viable life recorder, enabling the “life TiVo” and total recall capabilities explored by researchers such as Steve Mann and Gordon Bell. Continuous capture will be a tremendous accelerant for participatory media services, from YouTube and Instagram-style apps to citizen journalism. It will also fuel the already heated discussions about privacy and the implications of mediated interpersonal relationships.

Of course there are many other unanswered questions here. Will Glass be an open development platform or a closed Google garden? What is the software model — are we looking at custom apps? Some kind of HTML5/JS/CSS rendering? Will there be a Glass equivalent to CocoaTouch? Is it Android under the hood? How much of the hard optical and electrical engineering work has already been done? And of course, would we accept an even more intimate relationship with a company that exists to monetize our every act and intention?

The idea of a heads-up, hands-free, continuous model of personal computing is very interesting, and done well it could be a compelling advance. But even if we allow that Google might have the sophistication and taste required, it feels like there’s a good 3-5+ years of work to be done before Glass could evolve from concept prototype into a credible new computing experience. And that’s why I think Google has tipped their hand far too soon.

At yesterday’s Facebook press event launching new mobile features, Mark Zuckerberg stirred up a minor tempest in the pundit-o-sphere. When asked about when there would be a Facebook mobile app for the iPad, he responded glibly:

At yesterday’s Facebook press event launching new mobile features, Mark Zuckerberg stirred up a minor tempest in the pundit-o-sphere. When asked about when there would be a Facebook mobile app for the iPad, he responded glibly: