I love that we are on the cusp of a connected, augmented world, but I think the current crop of magic lenses are likely to overpromise and underdeliver. Here are some initial, rough thoughts on designing magic lens experiences for mobile augmented reality.

The magic lens

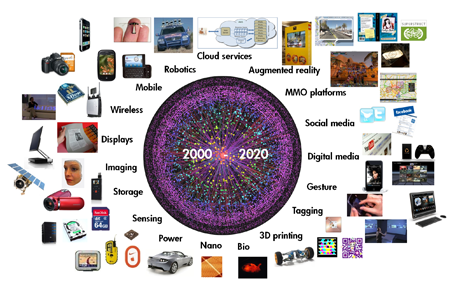

The magic lens metaphor [1] for mobile augmented reality overlays graphics on a live video display from the device’s camera, so that it appears you are looking through a transparent window to the world beyond. This idea was visualized to great effect in Mac Funamizu’s design studies on the future of Internet search from 2008. Many of the emerging mobile AR applications for Android and the iPhone 3GS, including Wikitude, Layar, Metro Paris, robotvision, Gamaray and Yelp’s Monocle, are magic lens apps which use the device’s integrated GPS and digital compass to provide location and orientation references (camera pose, more or less) for the overlay graphics.

The idea of a magic lens is visually intuitive and emotionally evocative, and there is understandable excitement surrounding the rollout of commercial AR applications. These apps are really cool looking, and they invoke familiar visual tropes from video games, sci-fi movies, and comics. We know what Terminator vision is, we’re experienced with flight sim HUDs, and we know how a speech balloon works. These are common, everyday forms of magical design fiction that we take for granted in popular culture.

And that’s going to be the biggest challenge for this kind of mobile augmented reality; we already know what a magic lens does, and our expectations are set impossibly high.

Less-than-magical capabilities

Compared to our expectations of magic lenses, today’s GPS+compass implementations of mobile AR have some significant limitations:

* Inaccuracy of position, direction, elevation – The inaccuracy of today’s GPS and compass devices in real world settings, combined with positional errors in geo-annotated data, mean that there will generally be poor correspondence between augmented graphical features and physical features. This will be most evident indoors, under trees, and in urban settings where location signals are imprecise or unavailable. Another consequence of location and orientation errors is that immediately nearby geo-annotations are likely to be badly misplaced. With typical errors of 3-30 meters, the augments for the shop you are standing right in front of are likely to appear behind you or across the street.

* Line of sight – Since we can’t see through walls and objects, and these AR systems don’t have a way to determine our line of sight, augmented features will often be overlaid on nearby obstructions instead of on the desired targets. For example, right now I’m looking at Yelp restaurant reviews floating in space over my bookshelf.

* Lat/long is not how we experience the world – By definition, GPS+compass AR presents you with geo-annotated data, information tied to geographic coordinates. People don’t see the world in coordinate systems, though, so AR systems need to correlate coordinate systems to world semantics. The quality of our AR experience will depend on how well that translation is done, and today it is not done well at all. Points Of Interest (POIs) only provide the barest minimum of semantic knowledge about any given point in space.

* Simplistic, non-standard data formats – POIs, the geo-annotated data that many of these apps display, are mostly very simple one-dimensional points of lat/long coordinates, plus a few bytes of metadata. Despite their simplicity there has been no real standardization of POI formats; so far, data providers and AR app developers are only giving lip service to open interoperability. Furthermore, they are not looking ahead to future capabilities that will require more sophisticated data representations. At the same time, there is a large community of GIS, mapping and Geoweb experts who have defined open formats such as GeoRSS, GeoJSON and KML that may be suitable for mobile AR use and standardization. I’ll have more to say about AR and the Geoweb in a future post. For now, I’ll just say that today’s mobile AR systems are starting to look like walled gardens and monocultures.

* Public gesture & social ambiguity – Holding your device in front of you at eye level and staring at it gives many of the same social cues as taking a photograph. It feels like a public gesture, and people in your line of sight are likely to be unsure of your intent. Contrast this with the head down, cradled position most people adopt when using their phone in a private way for email, games and browsing the web.

* Ergonomics – Holding your phone out in front of you at eye level is not a relaxed body position for extended viewing periods; nor is it a particularly good position for walking.

* Small screen visual clutter – If augmented features are densely populated in an area, they will be densely packed on the screen. A phone display with more than about 10 simultaneous augments will likely be difficult to parse. Some of Layar’s layer developers propose showing dozens of features at a time.

Design strategies for practical magic

Given these limitations, many of the initial wave of mobile AR applications are probably not going to see great adoption. The most successful apps will deliver experiences that take advantage of the natural technology affordances and don’t overreach the inherent limitations. Some design strategies to consider:

* Use augments with low requirements for precision and realism. A virtual scavenger hunt for imaginary monsters doesn’t need to be tied to the exact geometry of the city. A graphic overlay showing air pollution levels from a network of sensors can tolerate some imprecision. Audio augmentation can be very approximate and still deliver nicely immersive experiences. Searching for a nearby restroom may not need any augments at all.

* Design for context. The context of use matters tremendously. Augmenting a city experience is potentially very different from creating an experience in an open, flat landscape. Day is a different context than night. Alone is different than with a group. Directed search and wayshowing is different from open-ended flaneurism. Consider the design parameters and differences for a user who is sitting, standing, walking, running, cycling, driving and flying. It seems trivially obvious, but nonetheless important to ask who is the user, what is their situation, and what are they hoping will happen when they open up your app?

* Fail gracefully and transparently. When the accuracy of your GPS signal goes to hell, reduce the locative fidelity of your app, or ask the player to move where there is a clear view of the sky. When you are very close to a POI, drop the directional aspect of your app and just say that you are close.

* Use magic lens moments sparingly. Don’t make your player constantly chase the virtual monsters with the viewfinder, give her a head-down tricorder-style interaction mode too, and make it intuitive to switch modes. If you’re offering local search, consider returning the results in a text list or on a map. Reserve the visual candy for those interactions that truly add value and enhance the sense of magical experience.

* Take ownership for the quality of your AR experiences. Push your data providers to adopt open standards and richer formats. Beat the drum for improved accuracy of devices and geo-annotations. Do lots of user studies and experiments. Create design guidelines based on what works well, and what fails. Discourage shovelwARe. Find the application genres that work best, and focus on delivering great, industry-defining experiences.

We are at an early, formative stage of what will eventually become a connected, digitally enspirited world, and we are all learners when it comes to designing augmented experiences. Please share your thoughts in the comments below, or via @genebecker. YMMV as always.

[1] The idea of a metaphorical magic lens interface for computing was formulated at Xerox PARC in the early 1990’s; see Bier et al, “Toolglass and Magic Lenses: The See-Through Interface” from SIGGRAPH 1993. There is also a substantial body of previous work in mobile AR including many research explorations of the concept.